This article originally appeared in Canterwood Lifestyles

This article originally appeared in Canterwood Lifestyles

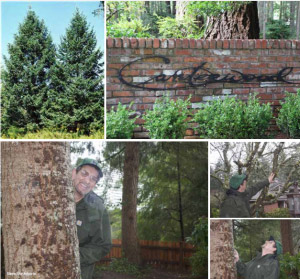

By Steve Wortinger Guest Writer, ISA Certified Arborist, Photos by Jan Kisla

Yes, there are giants in Canterwood … over 100’ tall and weighing thousands of pounds each. These gargantuan trees are Douglas firs — currently the second-tallest conifer in the world, after the coastal redwoods.

When you drive into the neighborhood the fir trees tower over all other trees, plants, buildings and homes. They reach out offering their branches like open protective arms to provide safety for all understory trees, plants and animals. They make our air fresh…our water clean and provide a majestic ambiance to our landscape.

The botanical name for this tree took years and years to figure out. You see, the Douglas fir is not really a fir tree at all. It has been called a pine, a spruce, a redwood, a hemlock and of course a fir, plus a few others “shots in the dark,” until it was finally agreed upon.

The native Americans that lived here when the Europeans arrived, the Salish, called the tree “La: yelp.” The Salish people said the cone looks like a small mouse is hiding in the end. (If you look at a cone closely, there are three little protrusions that resemble two back legs and a tail … the mice are hiding from an approaching fire!)

Early explorer, Captain Van Couver, had a doctor named Archibald Menzies on board his ship. Archibald had worked for the Royal Botanical Gardens as a naturalist and he was the one assigned to log and collect plants from the places this explorer and his crew visited. Archibald Menzies was the first person to bring citrus seeds to Hawaii and also was the first European to climb Mauna Loa on the Islands. We will return to Menzies in a bit….

David Douglas was 9 years old when Menzies was looking at trees in the Pacific Northwest. Douglas was from Scotland, as was Menzies, and Douglas, 40 years later walked in Menzies’ footsteps and became a rival naturalist and botanist. He even climbed Mauna Loa to become the 2nd European to climb it.

No one could identify this tree correctly, and, finally almost a hundred years later, it received a scientific name, Pseudotsuga Menzesii, commonly referred to as the Douglas fir. The name means False Hemlock, so Menzies got his name on it and Douglas got his name on it too. However, both were deceased when it was finally settled.

I specialize in Douglas fir because they are the ones that fall on you and part of my job is teaching people not to be afraid. Most people believe fir trees are dangerous because they can grow to 150 feet in height. Although that makes them dangerous when they fall, the reason they fall is not above, but below. Firs typically have a shallow root system compared with other trees, like cedars. When disease or old age hits, the root system will actually shrink, making them a pushover when the ground is saturated and a windstorm hits. The real danger is a diseased or damaged fir tree can look healthy to the untrained eye, despite years of suffering.

Signs for homeowners that Douglas fir trees don’t feel good:

- Happy branches turn up at the ends like a smile. However, if the branches flatten out, or frown, the tree needs a closer look.

- Cones should only be present in five-to-sevenyear cycles. Too many cones and the tree is telling you it is sick. Take a closer look.

- Needle cast, needles falling off everywhere — more than usual – is not a good sign.

- Color change. Compare it to other Douglas firs for deep dark green color. Lighter shades need a closer look.

- Bare branches in the upper canopy are an indicator of a possible problem. Lower branches die back from no sun. But, upper branches dying, need a closer look.

- Short sap runs all over the trunks is usually borer beetle exit wounds, and needs a closer look.

Healthy, properly cared for fir trees will not fall on you, or your property. However, we must understand that these trees are now part of a landscape, not living in the wild woods anymore. A client once asked me what was wrong with their trees and I pointed to the big house he came out of. We can live under these trees, but the Douglas firs need our help to survive. Feeding, mulching and watching for signs of decline is important in Canterwood. Most importantly, enjoy them – look what they went through to get their name!

(Steve was born in rural Indiana and attended landscape construction school in the San Francisco Bay area where he learned to draw landscape designs. A Washingtonian for over 20 years, Steve enjoys his 10-acre organic farm in Vaughn, where he harbors rescued animals and grows veggies. Over 30 years in the green industry has led to a specialized career as a Certified Arborist and expert witness for court cases. www.SteveArborist.com)